Hello and welcome back to TechCrunch’s China Roundup, a digest of recent events shaping the Chinese tech landscape and what they mean to people in the rest of the world. This week, Apple made some major moves that are telling of its increasingly compliant behavior in China where it has seen escalating competition, but investors are showing dissatisfaction with how it is approaching hot-button issues in the country.

Virus game gone

Plague Inc., a simulation game where a player’s goal is to infect the entire world with a deadly virus, was removed from the China iOS App Store this week. Since the outbreak of the COVID-19 coronavirus in late January, Chinese users had flocked to download the eight-year-old game, potentially seeking an alternative way to understand the epidemic.

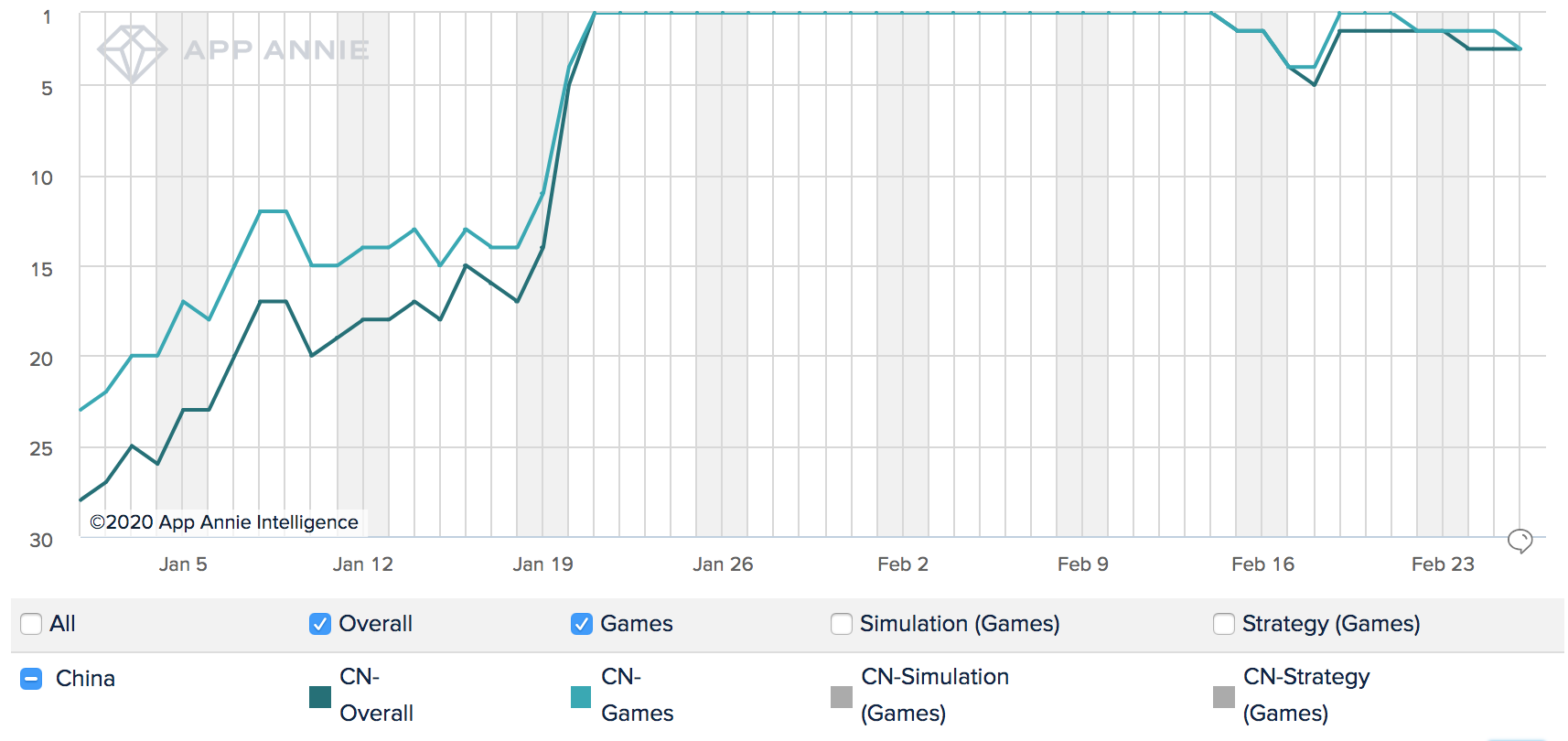

Data from market research firm App Annie shows that the title remained the most downloaded app in China from late January through most of February, up from No. 28 at the beginning of the year.

Ndemic Creations, the U.K. studio behind the game, said in a statement that the “situation” — the removal of Plague Inc. from the Apple App Store — “is completely out of our control.” The Chinese government provided an opaque reason for the takedown, saying the game “includes content that is illegal in China as determined by the Cyberspace Administration of China,” which is the country’s internet watchdog.

The incident has gotten plenty of attention in and outside of China. Some speculate that Apple has caved to pressure from Beijing, which could find Plague Inc.’s gameplay troubling. One sticking point is that its tutorial by default picks China as the starting country, although in the main game a user can begin anywhere in the world. The Information reported in 2018 that Plague Inc. actually applied for official permission to distribute in China but was turned down on account of its “socially inappropriate” content.

Others including Niko Partners games analyst Daniel Ahmad suggested that the Chinese authority might have taken issue with a December version update that allowed players to create “fake news,” which could mislead them in seeking advice in the midst of the health crisis.

Ahmad also suggested that the ban might have been linked to the ongoing crackdown of unlicensed mobile games in China. Notably, the Plague Inc. ban coincided with Apple’s announcement this week that would require all games in its Chinese app store to obtain government approval in the form of an ISBN number beginning in July. Few details have come to light about what this new regulatory process entails. Nor do developers know whether currently published games without official approval will be removed.

Apple investors are not sitting well with the firm’s app takedowns in China. 40% of its shareholders cast support for a proposal that would force Apple to uphold human rights commitment and be more transparent on how it responds to Beijing’s requests to censor apps.

Apple’s Delay

The gaming permit requirement is not new, though. In fact, Apple is just closing a regulatory loophole that had existed for years. Back in 2016, the Chinese government stipulated that video games — both PC and mobile — must apply for an ISBN number before entering circulation China. Within months, alternative Android stores operated by domestic tech giants swiftly moved to weed out illegal games. The official Google Play store is unavailable in China.

But Apple has managed to keep unlicensed titles in stock in the world’s largest gaming market, where content is strictly monitored. The American behemoth has many incentives to do so. Despite iPhone’s eroding share in China (to be fair, all Chinese phone makers but Huawei have recently suffered declining market share), iOS apps in China, especially games, remain an important revenue source for Apple.

So it’s in Apple’s best interest to clear hurdles for apps publishing in the country. Where there is a will, there is a way. Prior to 2016, publishing a game in China was relatively hassle-free. Following the regulatory change that year, Apple began asking games for proof of government license — but it didn’t go all out to enforce the policy. Local media reported that developers could get by with fabricated ISBN numbers or circumvent the rule by publishing in an overseas iOS App Store first and switching to China later.

This questionable practice did not go unnoticed. In August 2018, a Chinese state media lambasted Apple for its lousy oversight over App Store approvals.

Stepping up inspection on games will likely have little impact on China’s gaming titans who enjoy the financial and operational resources to secure the much-needed permit. Rather, their challenge is devising content that aligns with Beijing’s ideological guidelines, exemplified by Tencent’s patriotic makeover of PUBG.

Those that will be worst hit will most likely be small-time, independent studios, as well as firms that create “sockpuppet games” (马甲包), a practice whereby a developer exploits app stores’ loopholes to publish a troop of clones with similar gameplay and mask their appearance with altered names, logos and characters. Doing so can often help the publisher gain more traffic and revenue, but these sockpuppets will have a low chance of passing the authority’s strict scrutiny, which, as a Chinese gaming blog speculates, will potentially put an end to the surreptitious practice.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiUGh0dHBzOi8vdGVjaGNydW5jaC5jb20vMjAyMC8wMy8wMS9jaGluYS1yb3VuZHVwLWFwcGxlLWNsb3Nlcy1hcHAtc3RvcmUtbG9vcGhvbGUv0gFUaHR0cHM6Ly90ZWNoY3J1bmNoLmNvbS8yMDIwLzAzLzAxL2NoaW5hLXJvdW5kdXAtYXBwbGUtY2xvc2VzLWFwcC1zdG9yZS1sb29waG9sZS9hbXAv?oc=5

2020-03-01 16:55:44Z

52780638696147

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar