Half-Life: Alyx, Valve's first single-player game since 2012's Portal 2, is out now for virtual reality platforms. That has led me to write two separate articles. The first, a feature-length review, talks about the very, very good game in a vacuum; it assumes you have access to a relatively powerful gaming PC and a compatible PC-VR system.

This article, on the other hand, does not make that assumption.

What does it take to run Half-Life's VR-exclusive entry in March 2020? Which VR systems are the best? What's the best cheap way to dive in without spoiling the gameplay experience? And is HL:A reason enough to buy into the PC-VR space at this point? Let's dive in.

A refresher on the requirements

Let's begin with the bare requirements to play HL:A: a Windows 10 PC (sorry, Windows 7 holdouts) and a SteamVR-compatible PC-VR system. The former has a minimum level of system specs, which I'll get to later. The latter includes nearly every VR system on the market, with the obvious exceptions of PlayStation VR (which requires a PS4 console) and smartphone-shell solutions like Google Cardboard and Samsung GearVR. If a list helps, these headsets all work with the SteamVR software base:

- the full HTC Vive line (Vive, Vive Pro, Vive Eye, Vive Cosmos, etc.)

- Valve Index

- the full Oculus line (Rift, Rift S, Quest*)

- all Windows Mixed Reality-branded headsets (Samsung's HMD Odyssey+, etc.)

While Varjo's line of professional-grade VR headsets are advertised with SteamVR compatibility, we have not used any of them to test HL:A. I'll update this guide whenever I do (and Varjo has begun the process of shipping a loaner headset my way for temporary testing).

Since a lot of you will test with Quest, here's some nitty gritty

-

Oculus Quest as connected to the official Oculus Quest Link cable.Sam Machkovech

-

A better zoom at the new plastic clench that'll pair with the official Quest Link Cable.

-

Yes, my test was indeed running from a PC with a connected, wired tether.

Oculus Quest's listing has an asterisk because it's the only compatible headset to require additional hoops to get working. Both cost extra money. One additionally costs time and VR performance. As such, it's the only hardware to get a special "how to get working" section.

The simplest way to play HL:A with the "wireless" $400 Oculus Quest is to take advantage of its wired Oculus Link feature. (If you've never heard of Oculus Link, read my November 2019 explainer, then come back.)

The Oculus Link feature requires a cable with a USB 3.1 rating and a Type-C connector. The Type-C charging cable that comes in the Quest box is not rated for this speed (sigh). The cheapest one I've tested and confirmed working, a 10ft cable from Anker, is under $20 and in stock as of press time, while Oculus' own version is currently sold out. The best part about Oculus' version is its L-shaped connector, and while you can find similar 3.1-rated L-shape cables on Amazon, I can't attest to their compatibility or performance.

No matter which cable you use, you'll want to come up with a creative way to secure it to your headset or strap. Even with an L-shaped connector, its placement tugs on one side of your head in unideal fashion. Double-wrapped duct tape on the top of your headstrap is a bit clunky but at least moves the cable to a more balanced position.

Your other Quest option is to enable its wireless-VR mode. Before I explain how, I strongly urge you to not rely on this method. I tested HL:A via the Quest's wireless pipeline with an unobstructed 5GHz signal between my headset and my router, but this introduced consistent, obnoxious visual judder in the game's virtual world. Whether you're lining up a pistol's shot, spinning a puzzle's spherical base, or just trying not to puke after more than five minutes, this judder will spoil your experience more than any dangling cable off the back of your head.

With that out of the way, you'll need to purchase the Oculus Store's $14 version of the Virtual Desktop app, then download and install two apps: the Virtual Desktop Streamer app on Windows 10 and the "side-loaded" Virtual Desktop app for Oculus Quest. The latter is more complicated. Oculus Quest's OS runs on a fork of Android, which means you can download and install "unconfirmed" apps. While Oculus doesn't block this entirely, it requires that users register their Oculus accounts as "developer" accounts.

SideQuest, an unofficial side-loading resource for Oculus Quest, has a handy tutorial for toggling developer mode for your Quest. As part of this process, you can either install and use SideQuest's Windows app to install the Quest's custom Virtual Desktop app, or you can ignore SideQuest's app, follow steps 2-5 of its guide, and side-load the VD app yourself using the APK file found here.

While this unofficial wireless Quest mode is a fun party trick, it's not a great way to play HL:A. Other dedicated wireless-VR adapters are more expensive for a reason.

More controller flexibility than we'd expected, honestly

With Quest's mumbo-jumbo out of the way, I have great news. If you own any of the above compatible VR headsets, you can expect a serviceable method to play HL:A.

This is primarily because Valve scaled the game's controls down to the lowest common denominator: the four-year-old HTC Vive wands. You do not need a discrete joystick to comfortably play the game. You do not need the Valve Index Controllers' finger-tracking or grip-sensor gimmicks. You simply need a touchpad, a single trigger, and a single "menu" button on each controller to mimic the sensation of your real hands existing in VR. (Heck, you can play the entire game with only one Vive wand, thanks to the game's welcome accessibility features.)

Should your system of choice include joysticks, the game's "smooth motion" movement option works better. As my review points out, Valve gives players two control types: teleportation and smooth motion. The former is the default, and my preference. The latter resembles the kind of joystick control you'd find in a standard FPS video game, which some people may prefer, motion sickness be damned. HTC's Vive wands support this method, as well, but you don't get to anchor your real-life thumb on a convenient joystick when doing this. It's somewhat awkward as a result and not recommended.

In terms of comfort and button spread, the Oculus Touch, Windows Mixed Reality controller, and Valve Index Controller all get the job done, and they're also all shaped to fit comfortably into your hand—which mostly pays off when using the game's "cock to reload" mechanic for guns. This description also applies to the Vive Cosmos controllers, which launched with the Vive Cosmos headset in late 2019, but these are my least favorite controllers on the list. For starters, they're 63.5% heavier than Oculus Touch, at 211g with two AA batteries versus Oculus' 129g with one AA battery, and this difference is burdensome after a few hours of play. Worse, they depend on light tracking via RGB sensors, as opposed to most VR controllers' infrared sensing, which means the Cosmos pads always track a smidge slower and less accurately.

Even Windows Mixed Reality, whose headsets vary in terms of hand-tracked accuracy, is a better option across the board than the default Vive Cosmos option. You can also elect to get the Vive Cosmos Elite, which is compatible with the HTC Vive wands and Valve's Index Controllers, but I struggle to recommend Cosmos Elite at $900 for a full set (headset, HTC Vive wands, tracking boxes). The Oculus Rift has a slightly lower resolution but costs a whopping $500 less, while $100 more gets you everything that's superior about the $1,000 Valve Index.

-

The Valve Index Controller in my hand. I enjoy the sensation of opening my hands in the middle of a VR session, even just to relax them while waiting for something to happen in a game or app, but I typically rest my hand back on the grip portion.Sam Machkovech

-

The Index Controller's fabric strap fits neatly around the knuckles.Sam Machkovech

-

Valve's official hand models also show off the Index Controller with fingers on...

-

...and fingers off!

-

This dial can be pushed in to adjust the palm setting to one of four sizes. Getting this size right will ensure that your thumb rests comfortably on the big, touch-sensitive "pinch" button.

-

Another look at the palm-adjustment dial.

As I've previously said, the Valve Index Controllers are my current faves on the market. Just know that their perks within HL:A are about immersion, not control. They sell the sensation of physically interacting with so many objects, whether by letting you open your hands to "touch" a cabinet handle or reducing the requirement of physically holding a controller for so many hours (since they neatly cinch to your knuckles).

I get the feeling HL:A could have offered more interesting controls or systems if Valve had made this game Index-exclusive, and Valve devs confirmed in an interview with Ars Technica that at least one possible weapon upgrade was nixed for that very reason. For now, the game is better with Index Controllers, but not enough that other systems' users should feel the need to blow hundreds of dollars. (Index Controllers cost $280 as a standalone purchase, but they also require SteamVR tracking boxes and a SteamVR box-compatible headset. Meaning, they're not necessarily a cheap add-on for most users.)

Scaling to older PC-VR headsets

Do you have an older VR system, perhaps one you picked up when somebody sold their existing rig to shore up cash for a Valve Index? The good news for you is that HL:A scales quite well to older, lower-resolution headsets.

The game's emphasis on visual storytelling (mentioned in my review) mostly comes in the form of large posters, easy-to-read signs, and wide-open worlds. This is not a VR game full of books, notes, or other small-font text dumps that might require a newer pixel-rich headset to comfortably read. In bad news, the game does include a few Easter eggs that will require some serious squinting to appreciate on the 2016 class of PC-VR systems.

Should you use the original Oculus Rift, you'll need its additional Oculus Touch controllers (a different model than the Touch 2.0 controllers that ship with Rift S and Quest) and at least two Oculus webcam sensors. This model eventually shipped with Touch's controllers and extra sensor packed into the box, but if you're ordering a used system off sites like eBay, check that it includes the full Touch kit.

Most newer VR headsets, including some of my previous top recommendations (Oculus Rift S, Oculus Quest, Samsung HMD Odyssey+), include "inside-out" tracking systems. These remove the need for outside sensors and their respective plugs, and HL:A plays nicely with them. Meaning: you can play this game without waving your hands outside their typical "cone" of tracking (typically in front of, above, and below your face). You'll need to reach behind your back in real life to grab occasional virtual items, but HL:A is smart about recognizing when you do this. Even if it technically can't sense exactly where your hand is, it knows enough to fake the interaction with your "backpack."

The game's richly colored and diverse worlds look their best on the pixel-rich OLED panels of the Samsung Odyssey+ and the HTC Vive Pro, since every other headset relies on LCD panels and thus has issues with color saturation. Yes, that means the OLED options look richer than even Valve's impressive Index system, which is the best color-corrected LCD panel in the VR landscape but still can't beat OLED's color balance.

Valve Index and comfort: 15 hours add up

-

Valve Index, as donned on the author's head.

-

This strap doesn't reinvent the VR headset wheel, but it's plenty comfortable and evenly distributes the hardware's weight.

-

Pew pew.

-

Pulling the headset up to rest on your forehead is absolutely an option and works fine enough.

But Index has one useful perk that the others all lack: a wider, wisely engineered pair of display panels. The way these are arranged, and the way users can pull them closer to the face for a wider apparent field of view, adds a slight boost to peripheral vision. Also, these panels include the sharpest subpixel resolution on the market, thus reducing visible stairsteps between pixels, and their viewing angles offer the widest "sweet spot" of clear pixels across the board. Lastly, Valve Index's screens can render VR content at 120 frames per second, as opposed to most sets' maximum of 90fps. (The newest Oculus sets max out at 80fps on Rift S and 72fps on Quest, by the way.) And every non-Index headset has a slightly cocooned FOV and a smaller pixel sweet spot in comparison.

When playing quick-burst arcade fare like Beat Saber or Pistol Whip, these differences aren't necessarily apparent. Play for 30 minutes, take the headset off, and feel a slight bit of discombobulation for a few minutes as your eyes readjust to the real world. But Valve Index's various engineering tricks combine to make it easy to play for hours at a time without apparent eye strain. I previously turned the Index into my daily work monitor to confirm this quality, and it was borne out in reviewing the lengthy adventure of HL:A.

For this reason, I recommend Valve Index as the money's-not-an-issue headset for a hefty adventure game like HL:A. What you lose in the slight color boost of an OLED panel, you gain in longer-term usability. Other headsets will suffice, but I strongly recommend taking breaks every 90 minutes when using them.

Even with my number-one designation, Index comes with caveats. Valve Index is not quite as good at balancing its weight on users' heads as the Oculus Rift S' halo construction, and it requires setting up no less than two SteamVR base stations, since Index lacks inside-out tracking. While Valve insists that these tracking boxes deliver a superior VR experience, my preferred VR testing room has glass windows and a glass table, which I'm forced to cover with curtains and blankets since their glare otherwise interferes with the way SteamVR infrared tracking works. So I have the doubly annoying issue of extra power-connected tracking boxes and a litany of blankets I have to drape when I want to jump into VR.

Performance: What happens on the minimum spec?

The last major hardware category left is system requirements. Valve's official guidance on a minimum spec PC is pretty firm:

CPU: Intel Core i5-7500, AMD Ryzen 5 1600

GPU: Nvidia GTX 1060, AMD RX 580

Memory: 12GB (no speed listed)

The above GPUs and CPUs launched as lower-end, gaming-minded options in 2017 (except for the 1060, which arrived in late 2016), but they're also generally one step above the previous early-2016 minimum spec for SteamVR: Intel Core i5-4590 or AMD FX 8350 as CPUs, and NVIDIA GeForce GTX 970 or AMD Radeon R9 290 as GPUs. If you'd previously targeted the SteamVR platform's minimum specs, can you sneak into the HL:A party?

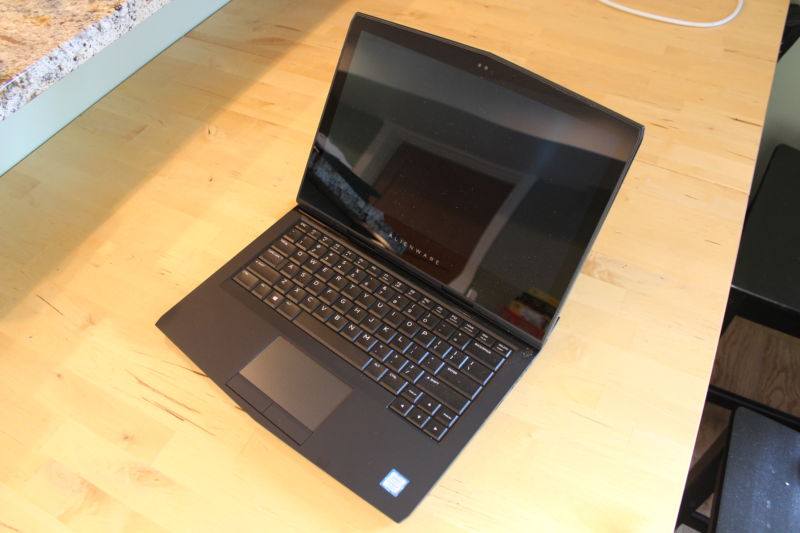

The outlook is hazy on that front. I've kept one testing system handy to test lowest-spec performance for VR: an Alienware laptop with an Intel i7-7700K and a notebook variant of the Nvidia GeForce 1060. This is an interesting one to test because it's technically on the edge of Valve's official guidance, but it's also contending with the thermal realities of a notebook chassis. In other words, it's up to snuff but can choke when higher-end games don't account for its limitations. Typically, this laptop does just fine with heavily reduced settings.

But on this laptop, with all settings slammed to lowest, HL:A still stutters as of one day before its retail launch. Its stutters aren't entirely consistent, as various on-screen action, geometry, and effects can drop frame rates below a comfortable 80 frames-per-second refresh on Oculus Rift S for three-second bursts. These are infrequent enough to make the game viably playable on the laptop in question. Plus, Valve may very well have optimization work to finish up for those riding on the performance edge, and I don't have enough of a testing lab setup to determine whether the issues are CPU-bound or GPU-bound.

That being said, if you show up with a machine on the minimum spec and turn all settings to "low," you're still in for a phenomenal feast of VR visuals and performance. Running everything on "low" on an RTX 2060 (not the "Super" variant) cruised at 120fps on Valve Index, thanks as much to its optimized engine as to SteamVR's ability to auto-select efficient in-game pixel resolutions, while key visual features (facial rendering, texture quality, view distances) still outclassed many VR games' "high" presets. Though I will say, the more VRAM you have, the better you'll fare in the textures department, which are a bit smudgy on "low" (6GB of VRAM) but make the world look noticeably better on "medium" and up (no less than 8GB of VRAM).

A virtual chicken and a virtual egg

The last point of consideration is how much content to expect that in any way compares to HL:A in terms of VR-exclusive, single-player content. It's no small qualm, as a chicken-or-egg issue has plagued VR game availability since its consumer-grade push emerged in 2016. Nobody's funding massive VR games because they think the audience isn't there, while the potential audience isn't buying headsets in droves because they don't see a ton of lengthy, high-quality VR games planned to launch in the next few years.

Once you've beaten Valve's new game, you won't have a ton of other options that compare well to HL:A's "only in VR" twists and adventure-length ambitions. My list of recommendations is short: Budget Cuts 2, the Oculus-exclusive Stormland, the "stare at your hero from above" adventure Moss, the brief-but-awesome Superhot VR, and the bolted-on VR perspective of No Man's Sky. The latter is a shoulder-shrug of a recommendation, as it's the best "PC game that works fine without VR" option to recommend if you find yourself starved for VR content. And I haven't listed must-own, quick-burst fare like Beat Saber, because "quick-burst" isn't the same category in the slightest.

(My recommendation list would roughly double in length if Sony ever loosed its PSVR-exclusive roster onto PCs. This includes the sensational VR version of Resident Evil 7, the stunning platformer Astro Bot: Rescue Mission, the puzzle classic Statik, and the thrilling, high-speed races of Wipeout Omega Collection.)

Other VR fare has come and gone with a range of ambitions, failures, and unnecessary padding. Not to single anything out, but last year's Boneworks is a good example of how small indie teams with huge ambitions have tried to advance VR as a platform, only to run smack into the logistical issues of making a hand-tracked game. VR games I've elected not to review at Ars over the past four years have fared much worse on that front.

Where are the other games, Valve?

The above slew of factors—headsets, controllers, PC specs, and hopes for more software—are reminders that anyone freshly buying a VR kit for HL:A is likely doing so as a raffle ticket for an uncertain future. This isn't like buying a new, next-generation game console, where you might expect a flow of "first-party" fare to keep your interest over a span of a few years. Valve makes amazing, lasting games (mostly) but simply doesn't operate at the same scale as a Sony, Nintendo, or Microsoft. And Oculus' first-party track record hasn't proven any better.

Luckily, Valve has never acted like VR's sole vanguards. The SteamVR creators have loudly embraced indie developers and have made no bones about its ecosystem playing nice with competitors' hardware and software. (Though Oculus has its own stupid walled garden, it's still not blocking the unofficial Revive toolset to launch Oculus games on other headsets.) But it's hard not to feel crestfallen about Valve's staff, expertise, and deep pockets falling short of a previous promise: three fully blown VR games. We've only gotten one at this point, with no word on if or when the other two may ever emerge.

Ultimately, I imagine rave HL:A reviews (which the game will undeniably receive from other outlets) won't move VR's viability as much as an even cheaper path to entry. Last year's $400 "all-in-one" Oculus Quest was a great start on the economic front. But HL:A understands that compelling, long-term VR experiences require a better-engineered headset and immersive, life-like visuals that Valve Index on a minimum-spec machine provides. Unless Valve wants to surprise us all with a Beyonce-style launch of those other two phantom games in the near future, the prudent answer for buying into PC-VR is still a piecemeal proposition.

If you've already built a recent gaming PC, you only have the additional cost of a standalone gaming console between you and serviceable HL:A gameplay. On the other hand, if you're behind on the PC-building curve and want to dive in at the higher end, you're likely buying the 3DO of our times.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiaWh0dHBzOi8vYXJzdGVjaG5pY2EuY29tL2dhbWluZy8yMDIwLzAzL3RoZS11bHRpbWF0ZS1oYWxmLWxpZmUtdnItaGFyZHdhcmUtZ3VpZGUtZnJvbS1mcnVnYWwtdG8tZmFudGFzdGljL9IBAA?oc=5

2020-03-23 17:00:00Z

CBMiaWh0dHBzOi8vYXJzdGVjaG5pY2EuY29tL2dhbWluZy8yMDIwLzAzL3RoZS11bHRpbWF0ZS1oYWxmLWxpZmUtdnItaGFyZHdhcmUtZ3VpZGUtZnJvbS1mcnVnYWwtdG8tZmFudGFzdGljL9IBAA

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar