Three years after receiving a record fine from the European Commission alongside an order to stop abusing its control of the Android operating system, Google is set to have its day in court.

Back in 2018 the company was fined €4.34bn (£3.8bn) for forcing phone makers to pre-install apps including Google Search and Chrome to the exclusion of other search engines and web browsers.

The fine was a fraction of the €116bn (£99bn) parent company Alphabet recorded in revenues that year, but the real cost to the company was the threat to its future income if smartphones landed in consumers' hands without Google apps already installed.

Google's five-day appeal against the decision is being heard at European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, where the company hopes to have the Commission's decision annulled in its entirety.

A failure to do so could completely reshape the smartphone landscape, but other challenges targeting Google inside the US pose a far more significant risk to the company and could lead to the search giant being broken up into several smaller businesses.

Breaking up monopolies

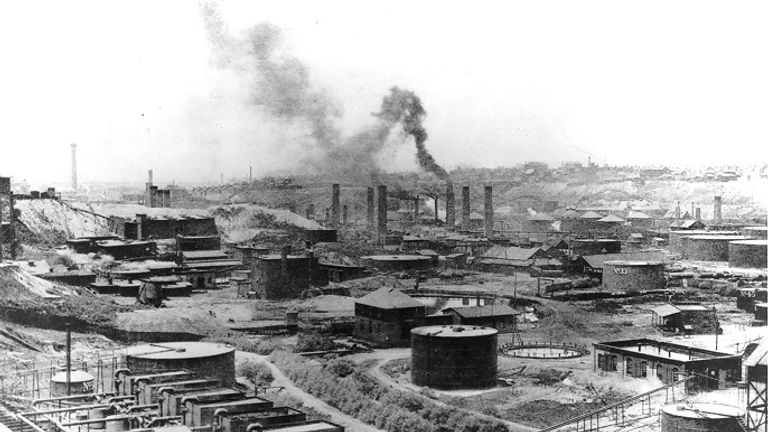

While there are an over-abundance of comparisons between the oil industry of the late 19th century and the tech industry of today, the slow movement of regulators is one of the most striking similarities.

It was in 1890 that US Congress passed a law to tackle the monopolies which had sprung up over the preceding half century, but it took more than three decades for that law to be used to break up Standard Oil, a company which by 1904 controlled more than 90% of oil production in America.

Standard Oil's business excelled due to its innovations in refining oil, but also because the company had rapaciously acquired rivals and used its commercial heft to strike deals with railroad companies (themselves a target for early antitrust action) at discounted rates which the remaining oil businesses could not compete with.

In a landmark ruling in 1911, the US Supreme Court upheld that Standard Oil was an illegal monopoly and ordered it to be broken up into 34 independent companies. Though that power is not available to the European Commission, there is a growing movement in the US calling for similar actions to be taken against tech giants whom some believe are guilty of the same anticompetitive practices.

Modern antitrust law

Google is a very different company to Standard Oil, but the alleged unfairness of its practices - using its control of Android to force phone manufacturers who want to include the Google Play app store on their phones to also pre-install Google Search and Chrome - follows the same model of undermining rivals.

The investigation into Google coercing phone manufacturers formally began in 2015, although the Commission made its first enquiries about the company's practices in 2013 when an association of Google's rivals calling itself FairSearch lodged a complaint against its business practices.

The ruling came three years later in 2018 and now, three years later, Google's appeal has reached the European Court of Justice. Thomas Vinje, counsel to FairSearch and partner at law firm Clifford Chance, told Sky News he expected there could be another appeal after the hearing in Luxembourg.

"Antitrust enforcement is not, on its own at least, sufficiently robust, sufficiently effective, to be able to address these really extraordinary concerns. I'm not sure the world has ever faced a situation where there is such a concentration of power in such a central element of today's economy, and antitrust law is not up to the task," he said.

"That is largely because they're complex cases," Mr Vinje explained.

"They're more complex than rail roads or oil distribution - I'm not saying those are simple - but the issues faced in Big Tech today are a hell of a lot more complicated. So there is a hell of a lot more room for obfuscation... and dragging things out.

"So by virtue of the completely appropriate rights that defendants have in these cases, the cases just take too long."

What is Google's response and appeal?

Google, which claims the most popular search term on rival search engines such as Bing is the word "Google" itself and which controls more than 90% of the market for web searches, disputes the Commission's arguments about its dominance, although that won't feature prominently in its arguments next week.

In a news briefing ahead of the hearing, the company explained to journalists that it believes a lot has changed in the years since the Commission issued its decision.

Key to Google's appeal is the argument that its control ensures Android is a platform which can run across millions of smart devices made by different manufacturers, increasing the economic benefits for developers - including rival web browser makers such as Opera, which is supporting Google's appeal - and ultimately consumers.

Google will note that a revenue sharing agreement it had with phone manufacturers and mobile network operators, cited as an illegal contractual restriction by the Commission, ended in 2014.

The company also strongly disputes the way that the Commission calculated the €4.34bn (£3.8bn) fine, something the Commission said was "calculated on the basis of the value of Google's revenue from search advertising services on Android devices" inside the European Economic Area.

A spokesperson said: "Android has created more choice for everyone, not less, and supports thousands of successful businesses in Europe and around the world. This case isn't supported by the facts or the law."

What is the threat in the US?

Even if Google succeeds in getting the Commission's decision annulled or amended, it faces three more challenges in the US which are backed by severe powers to tackle monopolies.

The first complaint was filed last October in a case led by the Trump administration's Department of Justice and joined by 11 states - though with apparent bipartisan support - charging Alphabet with "unlawfully maintaining monopolies in the markets for general search services".

It followed a congressional report which accused Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google of monopolising the digital market and recommended antitrust laws be used to break them up.

Two more cases were brought against Google in December.

One from the attorneys general of 35 states accuses the company of anticompetitive practices in order to retain its dominance in search, while another filed by the attorneys general from 10 states focuses on the company's monopoly power in digital advertising markets.

Google has denied engaging in anticompetitive practices.

https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMiiQFodHRwczovL25ld3Muc2t5LmNvbS9zdG9yeS9nb29nbGVzLWFwcGVhbC1hZ2FpbnN0LWV1LXJlY29yZC0zLThibi1maW5lLXN0YXJ0cy10b2RheS1hcy11cy1jYXNlcy10aHJlYXRlbi10by1icmVhay10aGUtY29tcGFueS11cC0xMjQxMzY1NdIBjQFodHRwczovL25ld3Muc2t5LmNvbS9zdG9yeS9hbXAvZ29vZ2xlcy1hcHBlYWwtYWdhaW5zdC1ldS1yZWNvcmQtMy04Ym4tZmluZS1zdGFydHMtdG9kYXktYXMtdXMtY2FzZXMtdGhyZWF0ZW4tdG8tYnJlYWstdGhlLWNvbXBhbnktdXAtMTI0MTM2NTU?oc=5

2021-09-27 09:33:45Z

52781903263800

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar